The Impact of Cognitive Distortion on Your Life

Imagine you just received good news and feeling ecstatic you go for a walk. Two steps away, you see a dear friend but you are not able to reach her.

Imagine you are at a party and you are having fun. Then, suddenly you feel you don’t fit in. Your ego just gave you a little reminder: “you are shy and boring”. It warned you to be cautious because people can notice and reject you. You quickly look for cues in the environment and of course, you find them. A girl is yawning and you stop talking to protect yourself from derision.

This might seem an extreme case, but in most circumstances, our ego makes a rapid appraisal of how we need to behave not to get hurt. It can be at a job interview, a first date, an animated discussion with our partner, a public event we are attending to.

In social psychology, the term ego refers to the self, the part of our identity that consciously defines the content of our self-concept, that is, the internal representation we created about who we are. I will refer here to the first definition of ego contained in the APA dictionary of psychology, and not to the meaning ego has in psychoanalytic theory (the Freudian Ego, Id, Superego).

In other words, the ego is the thinking part of the self that describes us with a list of attributes. The ego is our mind that perceives the self we think we are. The ego comes into play to make sense of reality, to explain what feelings, thoughts, behaviors are appropriate for the mental image we created of ourselves.

In a TED talk, Prof. Thomas Metzinger, philosopher, and cognitive scientist illustrates his book “The Ego Tunnel” ( Metzinger, 2014). He discusses the self using the terms ego and self interchangeably. He argues that what we believe is our own identity, the self, is essentially the content of a model created by our brain, a representational process we put in place to build up a robust experience of being someone. Whatever it is the content of the self-concept we created, it is experienced as something we own: my body, my feelings, my thoughts. To support his theory, he refers to the famous rubber hand illusion published by Botvinick (1998). He shows a woman who experiences a fake hand as part of herself and even feels a sensation of touch on it. From this illusion, Metzinger concludes that the self doesn’t exist and that our first-person perspective is just an illusion.

I wouldn’t go so far and suggest that the self-image our brain constructed is purely an illusion. The perception we have of our ego is the narrative of our life with its own achievements and projects. However, I believe that the rubber hand illusion indicates that our brain, sometimes, can misrepresent the nature of the self we think we are. I believe that similarly to the perception of our body, our brain can play tricks on us also when it comes to our own thoughts. After all, the brain controls our thoughts as much as it controls our body.

I know, it’s scary to even consider our brain plays tricks on us but it does to make sense of reality.

Consider the Checker shadow optical illusion designed by Edward H. Adelson (1995). The squares labeled as A and B appear in different colors when they are actually exactly the same color. This optical illusion is created by the way our brain understands contrast and shadow. But, even when we became aware of the trick and come to realize that the squares are the same color, our visual system can’t avoid but make a perceptive error. Our perception, consisting of sensation plus a good deal of interpretation, is the attempt of the self to make sense of reality. It is handy to have a coherent schema of who we are and what is reality, but this schema is far from being an impeccable and complete picture of reality. We continuously make perceptive mistakes that go unnoticed.

Despite the clear evidence of fallibility, we still entirely identify with our own self-concept and do not realize the limits of our own thoughts. As we take part in social interactions, we learn to protect and enhance our own ego as if our whole life totally depends on it. We believe that our drives and emotions must suit our self-concept.

We keep saying things like:

“I can’t make myself vulnerable to people because they can disappoint me”

“I can’t invite that guy because he might reject me”

“I can’t expose myself to people at that meeting, they might laugh at me”

In all these instances, we unconsciously distinguish between the “I” subject and the “me” object. To protect “me” (the ego, the self-concept), “I” need to fit in, look good, be accepted or I will get hurt.

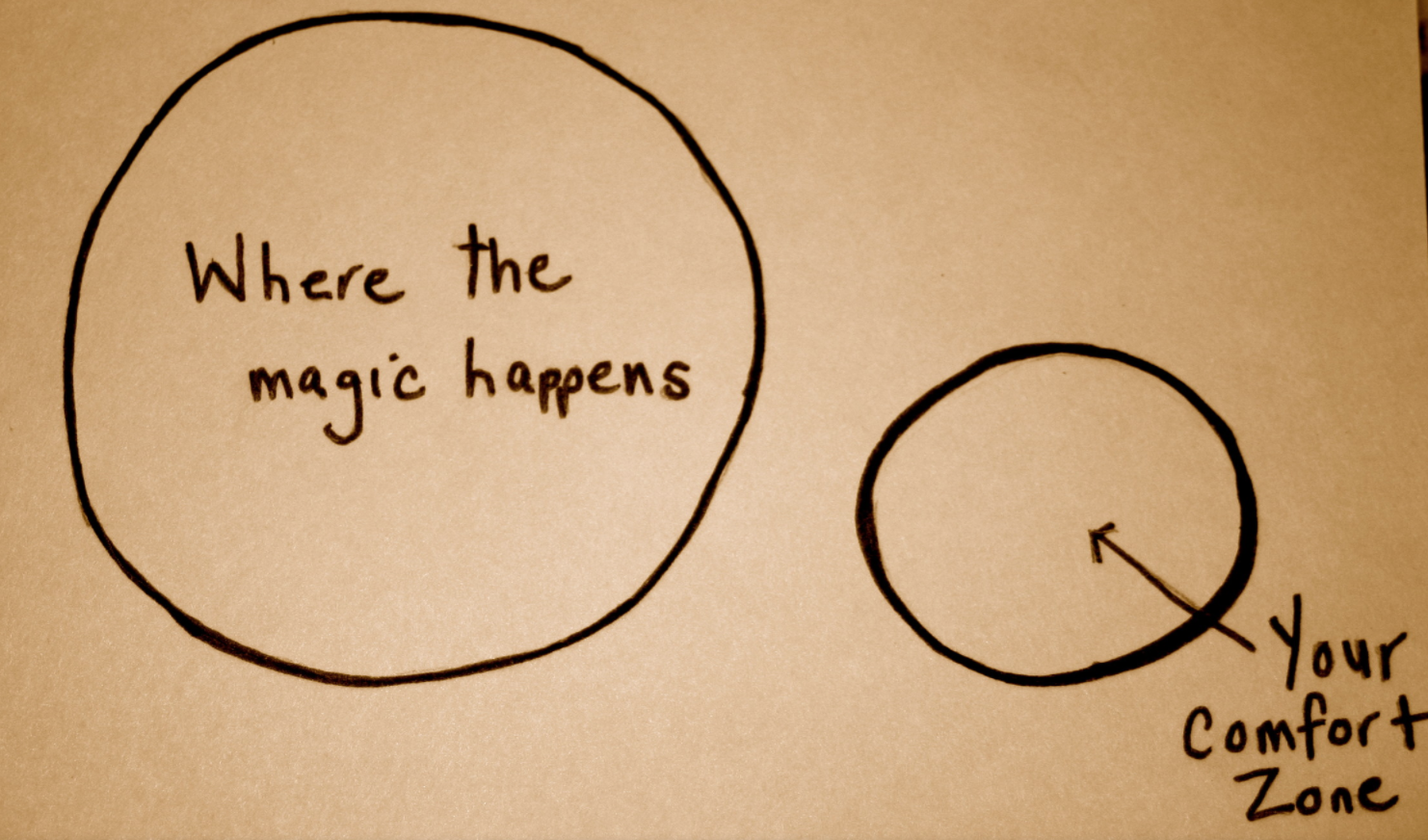

In all these instances, the same thoughts we make to protect our ego can cause confinement in our comfort zone. We actually stick to our self-image to claim a legitimate spot in that zone.

The comfort zone is defined by the management theorist Alasdair White (2009) as a “behavioral state within which a person operates in an anxiety-neutral condition, using a limited set of behaviors to deliver a steady level of performance, usually without a sense of risk”. Other definitions have been used, all pointing to the limits imposed by this behavioral state on our personal growth.

In our comfort zone, we feel safe and secure. Our emotions and feelings suit the representation our brain created about who we are, and, because we are not challenging our self-concept, we don’t feel stressed. But, that’s exactly when defending our ego causes us more troubles: we set limits to ourselves and we stop growing.

Most of the time, what holds us back is the frame of our mind, rather than a real lack of competence.

Addictive behaviors might be a good example of comfort zones.

“I have been a smoker my whole life, I won’t be able to stop.”

“I know I am obsessed with shopping, but that’s who I am.”

Addictive behaviors can be seen as coping strategies our ego put in place to defend us from nastier reality of life. When we defend our addictions, we live in the denial of short-term instant gratification. We think we are taking care of ourselves but we are only delaying more pain. We hold onto the perception our self-concept is immutable and we just have to accept it. We are actually just limiting our potential.

Addictive behaviors are only one example of comfort zone. Every time we hold back from crossing our limits, with the alibi that we can’t change, we are turning down the possibility that something amazing will happen to us.

Nobody says it is easy to break out of a comfort zone. But, it is possible. I think the first step is to stop defending your ego, stop identifying your entire self with your addiction. Stop seeing your addiction as a meaningful part of who you are. Just because it’s in your life history, it doesn’t mean it’s you. So, take a distance from it.

I also have comfort zones. For a long time, one of my favorites was my job as an oncology researcher. I lingered in there for too long before accepting that, despite a decent career, my love for science was going in other directions. To defend my comfort zone, I tried to fit in. I started to think I was just someone without intellectual curiosity, just a goal achiever without love. I started to defend my ego by thinking “a job is not everything in life” which is partly true, but I tried to convince myself it was entirely true. I wanted to believe it so badly so I could just stay comfy in denial. “A job is not everything in life” doesn’t mean you have to impose limits on your capabilities and stop looking for things that excite you. I was misusing this concept to defend my distorted perception of myself.

I came out of that comfort zone by making small steps. On day one it appeared impossible for me to stop my job and start a bachelor’s in psychology. That’s not how it happened. One day I started to imagine alternatives to my way of thinking: “I might be wrong” as Thom York sings. Another day I started taking distance from the way I represented myself for a long time. Another day I accepted that, although 37 years old, I still had some potential I was not entirely expressing. Another day I accepted that it’s good to change direction in life and that doesn’t mean you failed.

There is a book I found inspiring at that time: The Untethered soul by Michel Singer. I have to acknowledge it’s not the best book I have read and it’s not evidence-based. However, I liked the analogy that Singer makes between a comfort zone and a cage. We can feel the limit of the cage the minute we hit the bars. The bars are the boundaries of our comfort zone. Since we feel the pain as we come to the edge, we go back inside to feel secure. We prefer the cage because it is familiar, as opposed to the outside.

Here is the excerpt from another part of the book:

“There are two ways you can live: you can devote your life to staying in your comfort zone, or you can work on your freedom. In other words, you can devote your whole life to the process of making sure everything fits within your limited model, or you can devote your life to freeing yourself from the limits of your model.”

It’s illuminating to realize that staying in the comfort zone requires the same amount of work as taking the decision of leaving it. The only difference is that the comfort zone is familiar and the outside range of possibilities is unknown.

If we learn to distinguish ourselves from who we think we are and stop defending our ego, we will notice a shift in conscientiousness and come to the conclusion that we don’t necessarily identify with our thoughts but we can control them.

The moment we get defensive, we can decide to take distance and question our ego:

“Is it true I am shy, or am I just scared of rejection?”

“Is it true I can’t stop smoking or should I face the nastier realities in my life?”

“Do I really want to live my life below my potential?”

Only after realizing our self-concept is malleable, we can start having control over our life.

So, stop defending your ego, it causes more trouble than it’s worth!

References

Adelson, E. H. (1995). Checkershadow illusion.

Botvinick, M., & Cohen, J. (1998). Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature, 391(6669), 756–756.

Metzinger, T. (2014). Der Ego-Tunnel: Eine neue Philosophie des Selbst: Von der Hirnforschung zur Bewusstseinsethik. Piper Verlag.

Singer, M. (2007). The untethered soul: The journey beyond yourself. New Harbinger Publications.

White, A. (2009). From comfort zone to performance management.

Imagine you just received good news and feeling ecstatic you go for a walk. Two steps away, you see a dear friend but you are not able to reach her.

It’s hard to experience intimacy when these needs compete with love

© 2025 Rewired Life & Executive Coaching All Rights Reserved.

One Response

I was pretty pleased to discover this web site. I want to to thank you for your time for this fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every bit of it and I have you book marked to see new things on your web site.