Four Strategies To Help Your Brain Against Procrastination

I have been thinking to write a post about procrastination for a couple of months already, but every day I found a reason to postpone it: I wanted it to be good, and I anticipated my emotional discomfort from it not being as I hoped. So, I stretched as much as I could, procrastinating up until today.

I know I am not the only one. It is in the head of many of us:

“I should update my resume”

“I should start my self-care routine”

“I should learn how to use the new software at work”

“I should stop smoking”

However, most of us will not follow through on these commitments, not because we are lying to ourselves, but because tomorrow is always better than today to get started.

What exactly is procrastination and why it matters to us

Procrastination is defined as one’s voluntary delay of an intended course of action despite being worse off because of that delay. According to the latest reports, it is a pervasive habit affecting one-fifth of the adult population. An influential study conducted by Timothy Pychyl, a Psychology Professor at Carleton University, amasses evidence indicating that, in addition to low productivity, putting things off leads to all kinds of regrets, guilt, shame, and damaged self-esteem. As if this was not enough, realizing that we have not followed through with our commitments makes anxiety and self-blame pile up.

For all that is at stake, psychologists have been investigating what is happening in our brains that makes it so hard to act on our decisions.

If we judge an action to be the best for us, how is it possible that we do anything but that action?

Is our brain programmed to perpetually procrastinate?

Procrastination: a battle in your brain

Many people believe that procrastination is related to laziness or simple incompetence, but they could not be further from the truth. According to Pychyl, “Procrastination has a great deal to do with short-term mood repair and emotion regulation.” So, we put things off as a strategy to cope with the negative emotions prompted by a challenging task.

In this sense, procrastination can be traced back to our biology as the result of a constant battle between the limbic system, the oldest and most dominant part of our brain, and the prefrontal cortex, the newest part of our brain which separates us from other animals. While the limbic system plays a role in our automatic response to threats, the prefrontal cortex lights up when we make decisions, think about the future, and plan and execute complex behaviors.

In procrastinators, the limbic system often wins the battle.

Pychyl explains that when we face a task triggering negative emotions such as boredom, frustration, anxiety, or fear of failure, the amygdala, a vital part of the limbic system, perceives the task as a threat and overrides the prefrontal cortex, which consequently cannot plan or organize the executive functions it normally conducts. This phenomenon is known as Amygdala Hijack. A study shows that procrastinators tend to have a larger and more active amygdala which might explain their greater aversion to initiating tasks.

In addition to the amygdala hijack, in his article Psychyl presented evidence supporting a possible temporal disjunction between our present and future selves: we prioritize the immediate reward for our present self over avoiding negative consequences for our future self. When we feel drained, we expect the future self will not be as depleted and will be able to successfully manage the negative moods associated with a challenging or boring task that the present self cannot manage.

That said, our nervous system is plastic, including the amygdala. We can re-establish a balance between our automatic reactions to threats and our conscious and intentional executive functions to defeat unhelpful behaviors like procrastination.

So, if you are embarking on a journey to stop procrastinating, there are effective strategies to get in control

The following are four science-based strategies that I found extremely helpful.

1. Be aware of your negative emotions

A study performed by the group of Psychology Professor David Creswell indicated that mindfulness promotes functional neuroplastic changes in the amygdala. Over the course of three days, participants practiced mindfulness training that included body scan awareness exercises, sitting and walking meditations, mindful eating, and mindful movement. To foster mindfulness, instructors encouraged letting go of judgment and expectations, cultivating self-care, patience, and friendly curiosity toward the present moment experience. At the end of the training, people that practiced mindfulness had a different structure of the amygdala which entailed lower stress levels and better emotional regulation. People that did not attend the mindfulness training, the control group, did not change their amygdala.

Mindfulness is just one effective way to take control of your negative emotions. The emotional hijack can also be regulated by other practices promoting emotional and cognitive awareness, like coaching (better explained in the next paragraph).

2. Turn your rigid thinking (I must, I should, I got to) into flexible (I wish, I want, I like)

Sometimes being aware of our negative emotions is not enough if we are not aware of the rigid thinking that is triggering them. Rigid and extreme thinking, expressed as I must, I should, I ought to… is one of the reasons we procrastinate.

Sometimes being aware of our negative emotions is not enough if we are not aware of the rigid thinking that is triggering them. Rigid and extreme thinking, expressed as I must, I should, I ought to… is one of the reasons we procrastinate.

If we place too many demands on ourselves by experiencing everything as an obligation, a responsibility – even self-care – then we will constantly feel overwhelmed. As discussed by a group of psychologists that adapted cognitive behavioral therapy for use in coaching, low tolerance to failure and low tolerance to stress, as well as self-depreciation are the consequences of feeling constantly overwhelmed by our own rigid and extreme attitude.

Remember what happens when we feel stressed or threatened (yes, the idea of being a failure or not good enough both count as threats)? Our emotions take over our rationality: fear wins the battle and we put things off till tomorrow.

Do you also struggle with a rigid attitude where everything is an obligation?

For those willing to embark on a self-discovery journey there is a way out. When we allow ourselves to enjoy, like, wish, and desire, we shift to a non-extreme, flexible, rational mindset where:

- Mistakes are part of the game and an opportunity to gain experience

- Frustration and discomfort that come with starting a challenging task, are worth bearing to achieve our goals.

- We learn to accept ourselves and others because we know that a mistake does not define us.

- We learn to see nuances and perceive that humans are too complex to be defined by a single global rating.

A flexible mindset is the foundation of psychological health and is often at the core of a coaching journey. Rational emotive behavioral coaching (REBC) born from rational emotive behavioral therapy (REBT; Ellis, 1994) is one of the approaches within the field of cognitive behavioral coaching (CBC) that can help identify the rigid beliefs underpinning procrastination and develop flexible and non-extreme attitudes.

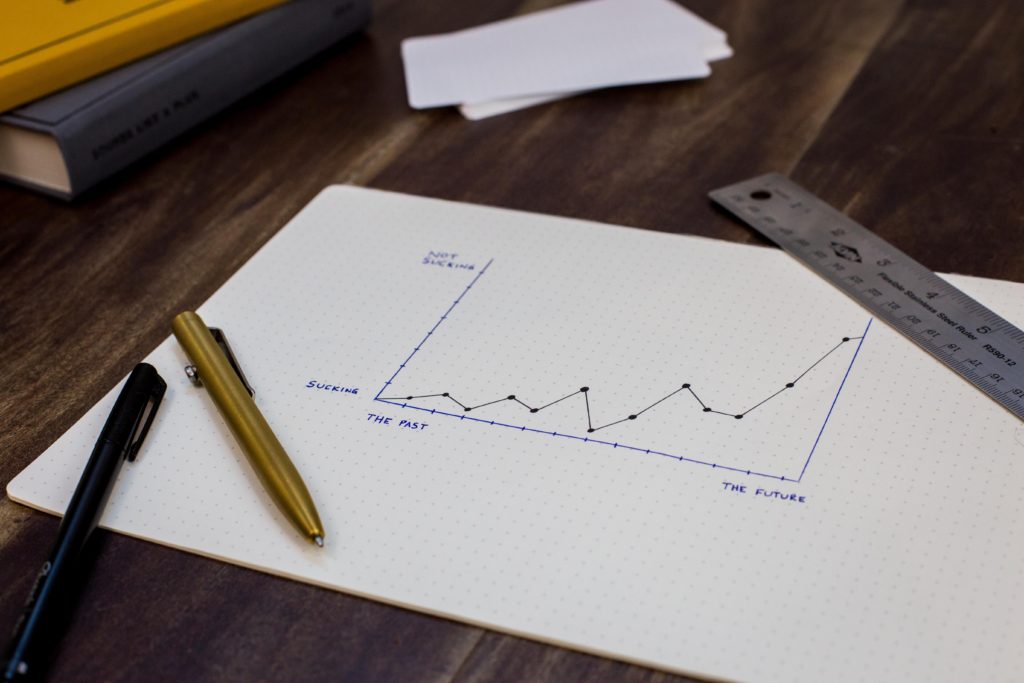

3. Chunk a complex task in small steps to make it less intimidating and to make your progress visible

Once you found your way to get control over your emotions (i.e., with mindfulness or CBC), it is time to move forward. Procrastination, whether it stems from fear or boredom, requires action.

Once you found your way to get control over your emotions (i.e., with mindfulness or CBC), it is time to move forward. Procrastination, whether it stems from fear or boredom, requires action.

The best way to follow through with action is to break the task into tiny steps. The trick here is to make the whole project less intimidating by forgetting about it and focusing on one chunk at a time. You need to trust the process because this attitude will really help you get started and make progress more visible.

After analyzing almost 12000 employees’ diary entries, Professor Teresa Amabile concluded that “The more frequently people experience that sense of progress, the more likely they are to be creatively productive in the long run”.

Amabile shows that when we make progress, even a small win fuels our well-being.

4. Support your rational brain by thinking concretely

According to a team of psychologists from the University of Konstanz in Germany, the way we think about an event, concretely or abstractly, impacts when the activity gets performed. So, if we represent something in abstract terms, as opposed to concrete terms (how I am doing it, where I am doing it, when I am doing it), we are more likely to procrastinate it.

According to a team of psychologists from the University of Konstanz in Germany, the way we think about an event, concretely or abstractly, impacts when the activity gets performed. So, if we represent something in abstract terms, as opposed to concrete terms (how I am doing it, where I am doing it, when I am doing it), we are more likely to procrastinate it.

In their study, participants were asked to respond to a questionnaire via e-mail within 3 weeks. The questionnaire was designed to induce either an abstract or a concrete representation of the task. Participants that received a concrete representation of the task were less likely to procrastinate. Importantly, this effect was shown regardless of the task’s attractiveness, importance, or perceived difficulty.

The researcher concluded that the level of abstractness and temporal distance are connected such that events represented abstractly are placed in the future, concrete events in the present.

So, to encourage action it might be worth representing the task as concretely as possible, thinking about why we want to do it, when we are going to do it, and how.

Takeaway

There is no quick-fix solution to stop procrastinating. The mentioned strategies require that you see procrastination as a barrier to your well-being and want to change. Once you are aware, you can pick the strategy that best resonates with you or explore them together. It also depends on where you are on your journey to overcome procrastination: start with awareness and emotional control, then go on with practical action interventions.

Share This Post

More To Explore

Inside the Mind: How Empathy Rescues a Hijacked Brain

The Amygdala Hijack and The Response of The Prefrontal Cortex

One Response

I was pretty pleased to discover this web site. I want to to thank you for your time for this fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every bit of it and I have you book marked to see new things on your web site.